murderer's eggs

He was a killer cook

After leaving the paved road I had some trouble locating the arroyo. It was dusk and the features of the land were all beginning to look the same in the Baja California desert. I made rapid drives up two or three openings in the terrain only to encounter rock walls. Finally, in the last of the light, I recognized a distinctive portion of the skyline of jagged hills up ahead that could lead us through the arroyo and into a valley. Across that valley, another arroyo leads past the remains of a deserted, old rancho, then into a canyon where lay the long abandoned Mission San Borja, Lucrezia Borgia’s legacy to the New World.

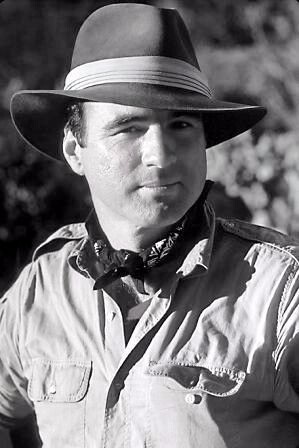

I was traveling with Garret Culhane and Matt Tully, two friends from school. Mathew is five foot, eight, with a beautiful physique and a perfectly silly looking tattoo of a cherub and a crescent moon on his right shoulder. His shoulder length hair and trim beard are both flame red. His hair is so thick and curly it looks like a seventeenth century cavalier’s wig. If he traded his gold rimmed glasses for a rapier and a dueling pistol the picture would be complete.

Garret grew up on a ranch in the California central valley, but he looks like he stepped out of an Ian Forster novel about turn of the century England. He is tall, lean and angular with black hair and neat mustache. His jaw juts forward handsomely. His favorite cloth is tweed. He is cerebral and reflective and tends to preface his questions with “Well now, Richard, let me ask you something.” He likes to have philosophical conversations that often become so convoluted he gets lost in them. He is also a first rate mechanic.

Garret and Matt were behind me in Garret’s rebuilt 1959 Willys jeep, panelled version. I led the way in my four wheel drive vehicle, the Argo. The normally clear skies were full of January clouds and a mist had risen from the ground. The sun had fully set and the darkness was so dense and so thick it was palpable. It gobbled up my headlight beams in mere yards. The recent annual rains had turned the dry water courses into gooey bogs and we would have to cross them in the dark. We crept along in low four wheel drive, keeping in close radio contact.

We had been rolling for over an hour when Matt radioed “Argo, be advised we are over-heating.”

“Cause?”

“Unknown. Will keep you advised.”

Within minutes he called again to say, “Argo, Argo! We’ve got to stop, we’ve got to stop, we’re red-lining

!”

“Ten-four,” I answered. “I’m coming to help.” I judged from the lights in my rear-view mirror that they were about forty or fifty feet behind me, so I cut the engine and hopped out and began walking toward the Willys. The mist was not uniform like a fog; it was a crazy mist, hanging in clumps and swirls with currents of clear air between them. It puffed up from the water courses and slid down hillsides and curled itself around the cacti and cirrio and other solid objects. It made the Willys seem much closer than it really was. I turned around and could no longer see the white form of the Argo.

When I reached the other vehicle the guys had the hood up, and in the reflected light of the headlamps I could see a stream of hot water drizzling down to the ground and making a big, steamy puddle. “Have you isolated the leak yet?” I asked.

“No,” Garret said. “It’s almost dry now. We’ll have to fill it up and try again. Let me ask you something, do you have plenty of water?”

“Five gallons. But from the look of that stream it won’t get us back to the highway.”

We filled the radiator and turned on the engine. Water gushed from a broken seam in the radiator’s exit port. The damage could hardly have been worse. If it were a broken hose we might have fixed it, as we carried a few spares; but this situation required our removing the radiator and then having it repaired by a welder. The nearest welder was in Guerrero Negro. I would need a full day to get there, a day to have the radiator repaired, and a day to get back. I would have to take Matt with me in case I should have some breakdown; or injury; or end up in jail; or who knows what. Garret would have to keep his own philosophical company in the desert for the next three days. Happy New Year.

Somewhere in the mist a dog barked. “Was that a dog?” Matt asked.

“Must be a coyote,” I said. “Got to be a coyote. No dogs out here.” The dog barked again. In the headlamp beams a puff of drifting mist began to darken and take form. As it came near it assumed the shape of a man with rifle. A dog shape trotted alongside. When he was still a silhouette he stopped and hefted the rifle in the crook of his arm.

“Quien es?” he hollered. Who’s there?

“Amigos,” I answered. “Hombres que nesesitan ayuda. Quien es usted senor?” “Friends. Men who need help. Who are you, sir?”

The shape paused. He said something to his dog, who then sat down and licked his chops. He came forward and with each step divested himself of mist. He came to within arm’s length and stopped. He was a short, dark man, strongly built, with a curly beard. He was scruffy and dirty and lost looking, and he eyed us with curiosity and delight, especially Matt’s bountiful cascades of firehair. He thrust a stubby hand out to anyone who would take it and said, “Manuel, me llamo Manuel. A su sirvicio, senores.” I am Manuel, at your service, sirs. He spoke no English, so I translated introductions. He told us he was living in the ancient rancho a few miles from the mission. He lived alone.

“Why are you carrying the rifle?” I asked him.

“Because I thought you might be cattle rustlers. I have a few head and I thought you might be after them.”

“Cattle rustlers, out here?” I asked.

“Who else would come here?” he shrugged. “Tell me, sirs. Why, in fact, are you here?”

We told him of our quest to San Borja, and then we told him of our trouble. He looked very excited and said, “Oh let me, let me.” He took my flashlight and crawled under the hood, half his body disappearing between the V-8 engine and the radiator. He fingered the breach, then came up smiling. I told him it needed “soldadura,” welding. “Maybe not,” he said, gesturing up the road. “At my ranchito I have a paste, an epoxy, that I mix together and use to repair metals. Maybe it can work to fix your radiator.”

I translated this to the others. Garret looked hopefully at Manuel and said, “Right now?”

“Ahorra mismo?” I asked Manuel.

“Please, gentlemen, it’s dark. It’s no time to work, or to drive in the desert.” Eagerly he said, “But I would be delighted if you would be my guests tonight. I can fix you some dinner. I can give you fresh eggs; I have chickens. You like coffee?”

“Hey, I’m for it,” Matt said. “I’m starving.” Matt is never not starving.

“How far is it?” Garret asked. “Will we have to leave the Willys behind?”

The rancho was only about fifty yards ahead of the Argo. Manuel ran ahead. When we rolled up a few minutes later he was rousting his chickens for all the eggs he could find. “Come in, come in,” he said with a sweeping gesture and a grin, as we walked into his kitchen. “Sit down. Be comfortable.” His little house consisted of this room and a bedroom. It was lit by a kerosene lamp and candles, and at the sink he drew water with a hand pump. All was dirt and dishevelment but, putting a hand on his heart and a pious look on his face he said, “I have very little; but what I have I give with all my heart.” Matt pulled a bottle of wine out of his jacket; Manuel glowed.

Manuel had collected six fresh, brown eggs, very large, and set about preparing them on his kerosene stove. “I have no tortillas, I hope you won’t mind. I’ll make you something similar to Huevos Rancheros. It’s my own dish.” He made a soupy Ranchero sauce of onions, chili peppers, garlic and tomato sauted in manteca. To that he added cooked macaroni. He broke three eggs into the pan of sauce. The others he broke into another pan and fried them, again using manteca. The eggs in the sauce were poached semi hard; those fried were sunny side up and the yolks ran when cut. He served us each a fried egg and a poached egg, both covered with the macaroni salsa.

I pushed some of my macaroni over onto the fried egg. I cut the egg up and swirled it, letting the fat, yellow yolk coat the pasta. The pasta was still hot enough to cook the yolk into a tasty glaze. On the other side of my plate I cut up the poached egg and mashed the yolk into the piquant sauce, making it thicker and more savory. The manteca gave the whole dish a rich smoothness and produced a warm and satisfying full feeling in the belly. Matt poured the rosy red wine and we feasted. Manuel beamed and politely tried not to guzzle the Cabernet Sauvignon.

After dinner we decided that whiskey was called for and Garret brought forth a bottle. Manuel was agog at his good luck. He had been living out there for months, he said, “with no comforts.” Garret poured healthy draughts all around and Manuel asked us to tell him our story. We described our lives to him, told him of work, of school, travel, war and peace. He followed each story with interest, he savored every detail. He had been starving for human company and this was nourishment for him.

He became effusive with good cheer. “My friends,” he said, suddenly inspired, “we have a custom where I come from. When men are friends, and they enjoy each other’s stories and food and drink, they exchange mustachios.” So saying he reached up to the corner of his mustache and, grabbing on to several whiskers, gave a snappy tug and yanked them out! Grinning, he held them forth between thumb and forefinger, the white roots like little flower bulbs at the ends of black stalks. “For you,” he said. Not knowing what else to do we each took one, muttering a confused “gracias.”

Manuel sat there grinning, looking at us each in turn, waiting for a response. With a shrug, Matt reached up to his mustache and ripped out a shard of hairs that made a sound like grass being pulled from the ground. “There you go, Manuel,” he said, “and one for all of you, too,” and he passed them around.

Garret seemed to think the whole thing hilarious said, “Ha ha. And here’s some for you,” as he reached for both ends of his mustache and tore out his offering, sharing them with all. Manuel collected his mementoes and promised to keep them in a special place. I was so glad that I was the only clean shaven member of this bizarre ritual of male bonding and said, “Damn! I wish I had a mustache!”

Lest this go any further and we start driving nails into our arms or slicing off bits of our flesh, I asked Manuel to tell us his story. He sat back for a moment and took a breath, as though gathering his powers. He requested a refill. Taking a sip, and rolling it on his tongue pensively, he spun out a long tale. He began: “I’m here, my friends, for gold.” We leaned closer. Taking another sip and gauging our interest he said, “I know gold. I know how to find it. It’s here, my friends, in these hills. The Spaniards, they were no good at finding gold. They built the missions and found souls to save but they weren’t good at finding gold. That’s why it’s still here,” he whispered, “and I’m going to find it.” He looked at his empty glass. Hands rushed to fill it.

He drew a lump of ore from his pocket and set it on the table. For a moment the only sound was breathing. “Look,” he urged. “Look. If you know gold, you can see I’m going to be rich.” We all leaned toward the quartzy piece of rock and peered into its interstices, as though it were a crystal ball, looking for a golden future.

“Let me have a closer look,” I said. “When I was seventeen I worked in a gold mine.” I picked it up and, turning it over said, “Mmm.”

“Does it look like good stuff?” Matt asked as Manuel sat proudly looking on.

“Mmm.”

“Well, what do you think? You think it’s the real thing?” Garret asked.

“Mmm.”

“Good eh?” said Manuel.

“Uh…mmm…er…I can’t tell. It’s been a long time since I worked in the gold mine, and that was just during summer vacation.”

Manuel took the ore and said, “I’ll show you.” He got up, a little woozily. Having been so long without “comforts” he was getting “comfortable” pretty fast. He dug through a wooden box and came up with a battered pair of binoculars. Looking through the big end he focused on the ore with the small end and said, “Here, look.” We all looked. We saw nothing, but said nothing. We just nodded, not letting on that we didn’t “know gold,” and wondering how you could know it by looking through the wrong end of a pair of binoculars. Manuel helped himself to more whiskey.

The liquor coursed through him, and he waxed expansive as he described all the things he was going to do when he was rich, all the places he would go, all the women he would have; they would all be blondes. Then he suddenly changed the subject. “You see that saddle over there,” he said, pointing to a ruinous looking pile of old leather. “Pancho Villa rode in that saddle. It belonged to him. You know Pancho Villa, the great general?”

“Oh yes,” we all nodded. “Pancho Villa, the great general.”

“He was from Sonora.” Manuel told us. “I’m from Sonora, too.” Lurching across the room he picked up his old rifle. I noticed that the butt was cracked and held together with electrical tape. He brandished it at us and said, “And this rifle was used in the Mexican revolution. It killed many men. Many men.”

Matt looked like he was going to hide the whiskey, but I grabbed it and poured Manuel the stiffest drink his glass could hold. “Salud,” I said. “Let’s drink to Pancho Villa, the great general!” Patriotically Manuel drank the health of the general, draining his glass. I refilled it.

“My friends,” said Manuel, “I told you I’m from Sonora. You know why I’m now in Baja California?”

“For gold,” we all said.

“Well, yes. But you know why I’m also in Baja California?” Cradling his rifle he sat down and eyed us all dizzily. Absentmindedly he reached into a pocket and pulled out a handful of bullets.

“Let’s drink to Sonora!” Matt said. Manuel, rifle in one hand and bullets in the other, considered his glass. He put the bullets back in his pocket and drank to Sonora. I refilled his glass.

Manuel continued, “I’m here because I killed a man in Sonora. He was an Indian. I caught him cheating me at cards. I didn’t have my famous rifle with me,” he said, patting it on the bre ach. “So I killed him with my knife. He was a big man, but I’m fast, and my knife was big. I don’t have the knife anymore because I left it in the Indian. Damned Indian,” he muttered.

His rifle was getting heavy so he leaned it against a wall and turned his attentions to his glass which I kept full. “Yes, I had to run from Sonora. The police wouldn’t get me because they’re my friends. I had to run from the Indians! So I went to Sinaloa. And what do you think? I killed another Indian, over a woman! This time the police wanted to get me, so I ran away to Baja.” His head drooping low, his face inches from the table, he murmered his last words of the evening: “And now I’m going to get rich and find gold.”

He sank into a little heap of whiskeysoaked flesh. We laid him in his lumpy bed and covered him with his filthy blankets. We looked at each other and sniggered. Pancho Villa’s saddle, a revolutionary rifle, two dead Indians and a lost gold mine all in one night; we’d never heard whiskey talk so much.

The next morning Manuel was up and about, hung over and still drunk at the same time. After giving us his epoxy he kept getting in the way of things, so we dispatched him quickly and painlessly with a few more drinks. After making our repairs we set a big lockback knife, as a present, on his table and left him sleeping. About a week later, in Bahia de Los Angeles, we met Don Guierrmo, who turned out to be el Dueno, the owner, of the land Manuel occupies. “Was he kind to you?” Don Gui errmo asked.

“Oh yes. He gave us dinner. And we gave him whiskey,” and we all chuckled.

“You gave him whiskey?” Don Guierrmo asked with visible concern.

“Uh…yeah. After all, he was very hospitable to us.”

“Senores. You should be very careful who you drink with around here. Manuel can be violent when he’s drunk. He’s already killed two men, that we know of.”

*********

So, okay, Manuel is, indeed, a murderer. He has conducted two of his fellows out of this world untimely to the next. Que vayan con Dios and Amen. But when he follows them he will, at least, have left behind his single, humble contribution to the happiness of the living. His little culinary offering stays active in my recipe file, where it frequently satisfies the appetites of my friends and garners me much praise. It was no less a personage than Brillat-Savarin, the great eighteenth century gastronome who said, “The discovery of a new dish does more for human happiness than the discovery of a star.” Even if the telescope is wielded by a man with the curse of Cain, the discovery is a worthy one.

Murderer’s Eggs

1/2 Spanish onion, diced

1 not-so-hot green chili pod, seeded and diced

garlic to taste, minced

6 oz can tomato sauce

1/2 cup cooked (al dente) pasta

2 eggs

1 Tablespoon cilantro, chopped

salt & pepper

manteca (You can use butter or olive oil and the result may be healthier but it won’t be as satisfying.)

Saute the vegetables in the manteca over medium heat till soft. Add tomato sauce, salt and pepper. A dash of Worcester is good, too. Cook five minutes over low heat. Stir in pasta and cilantro. Push the pasta outward from the center, making a space for the eggs. Break the eggs into the pan and cover them with sauce, being careful not to rupture the yolks. Cover the pan, reduce heat to very low and let the eggs poach three minutes.