Fortress of the ancient Warrior

An article for Baja Life magazine

The Sierra de San Fransisco rises almost straight up from the desert floor of Baja California, climbing for a mile. No rolling foothills presage its existence. It lunges up like skyscrapers, stabbing at the air with its crooked towers, snatching at clouds with its twisted peaks. Here and there high mesas contrast with the crags. The mesas fall away into great slashes of canyons, as deep as the mountains are tall. From the distance, the mountain range has the appearance of a huge mottled castle or fortress town, its high battlements cracked and broken by monstruous engines of war.

Before Cortez landed on this peninsula in 1535, long before the Aztecs ruled on the mainland, a wandering tribe had filtered into these mountains and stayed to live. They hunted deer and bighorn sheep, took water from the natural cisterns and rain catchments in the rock and gathered the many edible seeds that the arid land yields. They multiplied, they throve, they split into rival clans and made war. They practiced magic and the healing arts. Then they vanished. They left behind few artifacts, little detritus for archeologists to find. Not even the Indians who lived here when the Spaniards arrived knew anything of the lost people. The only significant evidence that they had come this way is in their hundreds of pictures on the rocky walls.

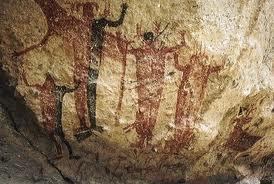

They painted pictures in caves and on cliff faces and rock overhangs. They are giant pictures, in Earth tone colors. Men and women are depicted as much as three times larger than life on rocky palletts so high that it seems only giants could have done the work. Animals are usually life size and they fight, they caper, they gather in herds. In one painting a huge serpent writhes along a cliff face for over a hundred feet. In another, a hemispherical outcropping of rock is cleverly painted to look like a shy tortise. He faces a dragonfly of exquisite beauty. Every crawling and walking animal and every bird that lived in these mountains is represented. I have even noted sea creatures. A whale swims vertically up a mountainside that faces the sea. Elsewhere a Yellowfin Tuna lies near a ram. And almost always, at least one giant human form broods over the animals, as if to reaffirm Man’s ascendance.

The first outsiders to see these paintings were the Jesuit missionaries looking to swell the ranks of the Spanish church. They wrote about them in their diaries, expressing satisfaction that, unlike the naked Indians they were dealing with, the painted giants appear to be clothed. The missionaries were able to keep the world at arm’s length from Baja, so nobody else found out about the paintings. When the Spaniards were expelled from Mexico, all outside knowlege of them ended.

The mission soldiers, artisans and their families were not included in the expulsion. Left behind, and without the material support of the church, many departed the mission lands, leaving several completely abandoned. They moved to the high mesas. They established tiny little hamlets where they subsisted by goatherding and small farming. The world passed by, Baja California fading from its consciousness. The fortress of the Sierra closed up its gates, sealed itself off and held on tightly to its secrets.

Erle Stanley Gardner, the creator of Perry Mason, was a Baja Bum. In 1962, he and his party were the first outsiders to penetrate the Sierra since the expulsion. They went to the high mesa settlment of Rancho San Fransisco de la Sierra. The people living there took the Americans to a cave where herds of painted animals thundered past giant men. A few years later, Harry Crosby, a teacher in San Diego, learned of the paintings and set out on muleback to find as many of them as he could. With the help of local guides he found scores of them. Paul Harmon and I went to see if we could find them.

This trip was our second attempt on the Sierra. We had tried before to find a breach in the mountain walls but we had had no luck. That was the only time my modified four-wheel-drive, the Argo, couldn't take me where I wanted to go. We realized that only a mule could negotiate that terrain. To get into the Sierra we would have to go to the oasis of San Ignacio and hire mules, burros and a guide. On our way there, with the Sierra on our left, I noticed something new in the land. A steep, narrow dirt road was snaking and switchbacking its way into the mountains. Plainly it was new, as construction gear lay about the road head. "I wonder how far it goes," I said.

"Let's find out," Paul answered.

We had plenty of supplies and fuel and it was early in the afternoon, so we turned onto the new road prepared to go whatever distance it might lead. Just before dark we arrived at Rancho San Fransisco de la Sierra. We were a mile high and among people who had yet to see an electric light.

The next day we met a twenty year old, consumptive muleteer named Fransisco "Pancho" Arce Ojeda. We told him that we wanted to look for "cuevas pinturas," painted caves. He said that he could guide us and would take care of hiring animals for us. "No podemos usar mi camionetta en su lugar?" I asked. Can't we take my truck instead? He lead us the short distance to the edge of the mesa. A deep canyon yawned, wide enough swallow stars. The drop down was almost sheer. A switchback mule trail, inches wide, zigzagged to the bottom. Pancho pointed to an area somewhere far below, smiled and said, "Ahi, nos vamos ahi." There, we're going there. "Su camionetta puede volar?" Can your truck fly?

"Okay," I said. "Mulas y burros." He went off to make arrangements.

The next morning, as we got our gear together, I said to Paul, "Looks like we'll have to sleep on the cold, cold ground this trip, Pablo."

"Heh heh heh," he sniggered in a way that said "I've got a secret. Heh heh heh"

"What are you chortling about?" I asked.

He held up a nylon bag and in the voice of Curly Joe of the Three Stooges said, "Nyuck nyuck nyuck. Air mattress, yeah."

"You S. O. B. ," I said.

"Oh, wise guy, eh? Nyuck nyuck nyuck."

We had everything packed, and I was filling my Spanish wine skin with Valpolicella when Pancho returned with three riding mules and two pack burros. We lashed the gear to the burros. I included my small ice box full of perishable food; I figured the ice would last at least two days. Some people would criticize me for not traveling light. But I insist on eating well, even on the trail. Paul pointed out that I should bring along a tarp since I "didn't have the foresight to bring along an air mattress." I told him to go to Hell, but packed the tarp anyway. He quickly made it clear that he wasn't going to let me forget that I would be sleeping on road apples and he would be sleeping in comfort. "The comforts of the Argo have made you too dependent," he said. "You have to relearn self reliance. Heh heh heh."

I took some brief comfort in the fact that Paul's mule turned out to be uncooperative. For instance, it wouldn't exhale enough to be properly saddled. Pancho and I had to work together on it. He shoved a knee into the animal's ribs while I gave a mighty heave on the cinch. "Ha!" I said to Paul. "Have fun on your mule." When we had all mounted and were just about to go, Paul's mule nipped at the flank of my mule which then took off like bat out of Hell straight into a cactus patch with me screaming, "Whoa!" I only had one foot in the stirrup and one hand on the bridle and spent the longest ten seconds of my life expecting to be hurled from the saddle into a prickly pear. Finally the beast stopped, realized where it was and walked calmly back into line.

Pancho signaled and led the way. I followed behind him and the burros and Paul brought up the rear. We quickly reached the edge of the mesa and picked up the steep and narrow mule trail and began the harrowing plunge into the canyon. At times the trail was less that a foot wide and my shoulder brushed against the canyon wall. The most stunning moments were when the sure footed mules negotiated the out-jutting hairpin turns of the switchback. Our bodies swung out in the saddle and seemed to hang in space above the chasm.

Occasionally the trail widened to two or three feet. In one of these wide spots we stopped to let the animals catch their breath, though we did not dismount. Except for Paul. He was mentioning something about his air mattress and I turned around to gesture sharply to him. That uncooperative mule of his finally exhaled. The cinch loosened, the saddle slid over and one very chagrined Paul floppped onto the ground in mid sentence about his mattress. I felt much better.

As the sun climbed, we descended. By noon the light was streaming down hot and fiercely bright. The canyon walls were almost devoid of vegetation. Only skeletal thorn bushes and knarley roots protruded. They scratched at our faces and tore at our clothes. A streak of dried blood clung to my cheek. The hot light reflected off the bare, pale rock and glared in our eyes.

By the afternoon, the bottom was coming near enough to make out details of the terrain. I could see individual cacti and the larger boulders. As we made our final, winding approach, I noticed, ahead and below, in a narow defile, a small cluster of thatched roofs and a patch of dark green. "Pancho!" I hollered up ahead to him. "Que es?"

"Un rancho de mis primos!" A ranch of my cousins'. Everybody in the Sierra, including his wife, is Pancho's cousin.

The patch of green was an orchard. Citrus trees, fig trees, pear trees and grape vines were growing, seemingly, out of the rock. As we approached I saw that the orchardist had brought in the earth from afar. He had built a retaining wall about three feet high. For months, maybe years, every time he went to where there was dirt he brought some back, in his saddle bags, in feed sacks, in jars, perhaps in his pockets, whatever he had with him at the time. Water trickled in through a sluiceway made of split and hollowed palm logs. Fruits hung heavy from the trees and the grape vines sagged with the weight of their vintage.

The five buildings of the rancho were made of whitewashed adobe. A corral held about forty drowsey goats, another a string of mules. The stiff palm thatch of the roofs hung well beyond the walls, forming large eves that helped to shade the compound. Domesticated wild flowers made bursts of color in the courtyard. The narrow defile in which all was situated is called a "rincon." Literally it is the Spanish for "corner" or "nook." But it has connotations of refuge and safety, as though being in the bosom of something.

We were invited to dismount and take the shade with the residents of the rincon. They were a very old couple, their middle aged son and his wife, another woman a bit younger than the wife and a boy of about fourteen. He seemed to suffer from something like Down's syndrome. He sat dully in a room in one of the cool adobes, staring at nothing, a metal bowl tied to his head. Occasionally he groaned or grunted and lunged with his head toward a wall. All in the Sierra are cousins.

The old man and woman were both infirm. They could no longer walk nor ride. And so they could never leave the rancho. They would die there. Their bodies would washed and dressed and wrapped in shrouds by the younger people. They would be lashed to the backs of burros and taken to the high mesa for burial. A few years earlier they would have to have made the three day journey to San Ignacio to find hallowed ground.

We sat on solid, old wooden chairs in the patio, and conversed a little while in low tones; the rincon held no other noise to compete with our voices, and the accoustics were very fine. The senora served us oranges and lemons. I thought the lemons were to take with us, but she urged us to eat them. Not wishing to seem ungracious, I peeled and sectioned one as she watched, smiling. I thought I might have been in for a joke but when I bit into the fruit it tasted like lemonade with bitters. It was not quite sweet, and tart rather than sour. Its clean taste was like dry sparkling wine and as refreshing as cold spring water on a July afternoon. I greatly preferred the bittersweet lemons to the sweet, but seedy, oranges, and ate two or three.

The sun was in its long slide down and darkness would fall suddenly in the depths of the canyon. We took our leave and hurried on to find a camp site. About sunset we found a clearing, and while Pancho tended to the animals Paul and I unlimbered what gear we would need for the night, rolled out sleeping bags and built a small fire ring. We don't build any roaring bon fires in the desert. Fuel is too scarce unless you've brought your own. The practice here is to build a small fire and sit close.

We went looking for the twigs and sticks that would be our fire wood. It was that late hour in the desert, just before dark, when the air is gold and the thin streaks of high Cirrus clouds are tongues of flame. Shadows gather and disperse and gather again and the world is in flux, between two states of being, groping for its place. At the foot of a pile of huge boulders, Pancho stood in the shadow world, one foot in the daylight, one in the night. "No lo veas?" he said. Don't you see him?

He didn't point or otherwise indicate any direction. But our eyes traveled up the sloping pile of boulders to where its apex met the canyon's rock wall. Above that point, sheltered by overhanging rock, the ancient warrior stared down at us. He looked ten feet tall. Painted in brown, black and red, his form was like a ghost. His hands were raised and he was shot with arrows, one through the heart, another through the gut. Animals and men danced around him. Then the Night assumed its watch, and all became dark.

Clutching our bundles of sticks, we silently followed Pancho the short distance back to camp. We made a teepee of twigs in the fire ring and set them aflame. I found my wine skin full of Valpolicella and we all passed it around. We had said little or nothing since seeing the man of the arrows, but finally Paul and Pancho wondered what the painting signified and asked if I had any idea.

"No," I told them. "Nobody knows. We can only guess. The Catholics have a Saint Sebastian of the Arrows. His death was a sacrifice and he's considered a martyr. He's always depicted at the moment of death, with arrows sticking in him. Maybe this is some prehistoric version of something similar. Or maybe some one like Prometheus, another sacrifice, a suffering giant bound to the rock by Zeus for his unauthorised service to man. Who knows?"

"Maybe it was a warning to other tribes to stay away," Paul offered.

Pancho suggested that it might commemorate a victory in battle.

"How about a record of bad marksmanship while hunting?" Paul joked. "It says, 'Don't let this happen to you. Keep the safety on. '"

"Now that you mention it," I said, "some scholars believe the paintings were used as hunting magic. They theorize that game was chased or herded to these painted places, and that only here would they be killed or eaten."

"Then we're in their killing and feasting ground. A fit place for us to dine, I guess," Paul ventured.

"I guess. Whoa! Wait a minute," I blurted. "Think of the possibilities. If this is, indeed, a killing and a feasting ground, and the painting is of a man being killed and animals going free: then who is killing and eating what, or whom?"

"Ooh."

"Aye aye aye."

"Let's have another swig of wine and then some dinner," I said. The others approved, especially of the swig. I gathered my cast iron pot and wooden spoon, my pantry box, spice box and ice box and a mesh bag of vegetables.

"Que preparas?" Pancho asked. What are you making?

"Cassoulet," I said with gusto.

"Que es eso?" What's that?

"Uh, mmm. Frijoles frances." French beans.

Using my Buck knife I cut up a Spanish onion, a green bell pepper and some garlic. I didn't have a cutting board so I just whittled on them till they were all reduced to small pieces. From the ice box I took out three Italian sausages and four Oscar Mayer Smokey Links. I removed the skins from the sausages and cut the links into small slices.

I set the skillet on the fire and when it was hot put in the sausages, breaking them up with the wooden spoon and browning them. To that I added the vegetables and a little olive oil and sauteed them till tender. The Smokey Links went in next.

Having breathed the pure air of the canyon all day, the spicey, smokey smells that rose from the pan were especially potent. They wafted into our nostrils and found their way straight down to our stomachs, making them growl with anticipation. My salivary glands worked non stop, constantly filling my mouth as all the good things sizzled in the pan. I took frequent nips from the wine skin and held the wine in my mouth. I rolled it around, my tongue kneading it, jaws almost chewing it. I swallowed it the way you might swallow ice cream: tongue pushing it to the back of the throat a little at a time. After swallowing, the remnant vapors travelled from mouth to nasal passages, reminding me for minutes of its excellent, tart and fruity flavor and its undercurrents of cinnamon and black cherry.

Having lined up my remaining ingredients, I put them into the pot one by one. A small can each of kidney beans, lima beans and white beans for substance; a spoonful of prepared mustard and one of brown sugar to duel with each other across the pallett; parsley, bay and thyme for a traditional bouquet garni; Worcester and Tobasco just because; and stewed tomatoes and tomato paste to make a thick and savory sauce that would marry them all together.

The little fire was at perfect pitch for simmering, so I stirred the pot and let it alone. We sat on the ground and passed the wine skin back and forth. We emptied and refilled it. When the beans were done we removed the pan and sat closer to the fire. We each took a spoon and a Sierra cup and scooped up our portions. We ate slowly, enjoying the chew of the meat, the mash of the beans and the spicey, tomatoey bite of the sauce.

The moon rose. With the help of its light, when the fire flickered just so, we caught fleeting glimpses of the giant Hombre de las Flechas, Man of the Arrows, staring down at us. "I wonder how often his fellows feasted under his gaze like we are?" I said. "I wonder if he wanted to be remembered? I wonder if he was a real man, or a god, or an abstraction?"

"Funny," Paul said. "All he is is a question. There are no answers in him."

We finished our meal and our wine, and as we would be rising at dawn, we prepared for sleep. There were many other paintings that Pancho was eager to show us. Paul kept alternating between "Heh heh heh" and "Nyuck nyuck nyuck" and "Don't lay on any road apples." I crawled into my bag to find that I was, indeed, lying on a road apple. I bolted up and retrieved it and threw it at Paul, narrowly missing him. "Oh, wise guy, eh. Nyuck nyuck nyuck," he reponded. "And now the comfort king will prepare his boudoire." His face brimming with satisfaction, he opened his nylon bag and dumped its contents on the ground. It was a rolled up inner tube.

Heh heh heh. Good night, Pablito. Heh heh heh.